|

|

BOOK

REVIEW

Poetry

and Revolution: Behind Bars and Beyond

Jose Maria Sison’s poems are suffused with various kinds of imagery, but in

these one thread is common – the voice of a poet not only resolved to write

good poetry, but also revolting against oppression in all its forms. He thus

shares, in Philippine literary history, a place with the likes of Andres

Bonifacio, Jose Corazon de Jesus, Carlos Bulosan, Amado V. Hernandez, Eman

Lacaba, Lorena Barros, and Romulo Sandoval.

By Alexander Martin Remollino

Bulatlat.com

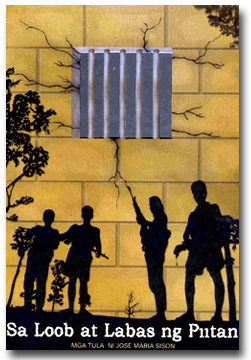

Recently made available to aficionados of protest poetry is Sa

Loob at Labas ng Piitan, Gelacio Guillermo’s Filipino translation of Jose

Maria Sison’s anthology Prison and

Beyond – which won for him the Southeast Asia WRITE Award in 1986.

Published by the Amado V. Hernandez Resource Center (AVHRC), the book was

launched last May 25, at a tribute to Sison held at the University of the

Philippines (UP) – where the revolutionary leader obtained bachelor’s and

master’s degrees in English Literature with honors.

Recently made available to aficionados of protest poetry is Sa

Loob at Labas ng Piitan, Gelacio Guillermo’s Filipino translation of Jose

Maria Sison’s anthology Prison and

Beyond – which won for him the Southeast Asia WRITE Award in 1986.

Published by the Amado V. Hernandez Resource Center (AVHRC), the book was

launched last May 25, at a tribute to Sison held at the University of the

Philippines (UP) – where the revolutionary leader obtained bachelor’s and

master’s degrees in English Literature with honors.

Sa Loob at Labas ng Piitan contains

both English and Filipino versions of the poems in Prison and Beyond. That way, the reader not only gets the feel of

the poems in both languages – he or she also sees how it is possible to

translate, as Guillermo was able to do so, from one language to another almost

literally without losing a single piece of the work’s essence. For another,

international readers can have some help in studying the Filipino language with

this book.

The book also has as appendix the poem “Chemistry of Tears,” which is not

known to have been previously published.

But more than that, the reader gets from these poems an idea of how Sison – as

a writer – has lived his avowed literary conviction. “I think that great

literature in different ages in the world and the major works so far written in

Philippine literary history assume significance, social and historical, insofar

as they are committed to the cause of freedom and they reflect with profound

insights the social conditions and the struggle for greater freedom,” Sison

said in a message sent to the UP Writers Club when he was still in detention in

Fort Bonifacio during martial law.

As

founding chairman of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), Sison was a

very hot item on the military list even before martial law was declared in 1972.

He would be captured by the military in 1977, imprisoned and subjected to a long

ordeal of physical and psychological torture.

Behind

bars

With

the exception of a few selections from a 1962 volume, Brothers and Other Poems, the pieces in Prison and Beyond were written when the author was behind bars.

Sison, denied pens in his first year in jail, at first composed poems in his

head as a way of fighting, preoccupying himself, and keeping his sanity. When

after a year ball pens were made available to him, he wrote down the poems he

had committed to memory and had the bright idea of hiding them in a lining in

his cot or in his pocket, for eventual distribution through lawyers and other

visitors.

Prison was surely an unforgettable experience for Sison, and this is reflected

in the title of the book itself as well as many of the poems in it.

In the 30-stanza “Fragments of a Nightmare,” which is written from a

first-person perspective, the persona talks of being made by “demons” into a

punching bag, of being threatened with death or more inhuman treatment, even of

being cajoled into running “for an assembly/Of demons.” The persona does not

identify himself and the poem has been the subject of dispute in certain

literary circles, but one thing is clear: the “I” speaking in “Fragments

of a Nightmare” is none other than Sison himself, as may be gleaned from the

book The Philippine Revolution: The

Leader’s View as well as Grace B. Salita’s interview with him last year

for her masteral thesis at De La Salle University. The “demons” are his

tormentors and others he considers the enemies of the Filipino people.

The author’s wife, Julieta de Lima, was captured with him in 1977, but for

years they were kept in separate cells. In “You are My Wife and Comrade,”

Sison speaks of the anguish from this experience thus:

You are my wife and comrade.

It is harsh that we are kept apart

By a bloodthirsty enemy with many snares.

We care for each other’s welfare.

The wishes of the tyrant are so evil.

He seeks the betrayal of our souls

By torture and the threat of murder

And the wasting away of our youthful vigor.

His cruel minions are gleeful

That we suffer in stifling cubicles.

They are driven by usurped power

And like dogs carry out orders.

But despair Sison does not here. There is determined defiance in the following

stanzas:

But even in our forced separation

We remain one in our fierce devotion

To the noble cause of the revolution.

Firmly the struggle we must carry on.

Our chief tormentor on the throne

Will someday be overthrown

For the seed has been sown

And the future is well-known.

(The poem was written in 1978. Eight years later, the Marcos dictatorship would

be ousted through a popular uprising.)

The theme of prison serving to strengthen character instead of breaking it is a

favorite of Sison. This is the theme behind his poems “A Furnace” and “In

the Dark Depths.”

‘Tis a seething furnace

For tempering steel

And purifying gold,

‘Tis a comforting metaphor.

This is what Sison says of his cell in “A Furnace.”

“In the Dark Depths” he describes his fellow political prisoners’ life

thus:

The enemy wants to bury us

In the dark depths of prison

But shining gold is mined

From the dark depths of the earth

And the radiant pearl is dived

From the dark depths of the ocean.

We suffer but we endure

And draw up gold and pearl

From depths of character

Formed so long in struggle.

In “Chemistry of Tears,” Sison goes beyond the prison imagery. He tackles

the theme of injustice breeding revolutionary armed struggle, with touches of

science:

Tears have too long been

the food of the meek.

But hunger has become

anger so fierce,

Turning the tears of the meek

into nitroglycerine

To explode the vile system

of terror and greed.

Such is the chemistry of tears

catalyzed by iniquity.

If “Chemistry of Tears” contains allusions to chemistry and physics, the

images in “From the Philippines to Vietnam: Birds of Prey”- written in 1967

at the height of the U.S. war against Vietnam – are biological:

Curse the birds of prey

That drop their iron eggs

Wantonly

That crush the fields

Viciously

Sowing hunger

Hatching death

Ripping the breast

Of our dear brotherland.

Vietnam! Vietnam!

Every bomb on your breasts

Is a blow on our hearts.

The crags of terror

Are in Mactan, Clark Field

Sangley Point and manywheres;

The nests of evil here

Comfort the black birds

That torture you.

Isabelo

de los Reyes

But

science is not the only field from which Sison draws allusions. He apparently

shares the interest of fellow Ilocano and scholar-activist Isabelo de los Reyes

in folklore, as shown in the poem “Angalo, O Angalo!” about a giant hero of

Ilocano legend whom he describes as a “Timeless foe of the oppressor.”

Leafing through Sa Loob at Labas ng Piitan,

one may notice that the poems written from 1962 onward – are more direct in

their language than those created in 1958-1962 – the ones lifted from Brothers

and Other Poems (“By Cokkis Lilly Woundis,” “Carnival,” “The

Imperial Game,” “The Massacre,” “These Scavengers,” “Brothers,”

“The Dark Spears of the Hours Point High,” and “Hawk of Gold”) –

although by no means are they less poetic.

From 1958 to 1962, Sison’s poetry tended to be somewhat elusive like much of

the period’s poetry, although even then it already contained deep insights

into social realities of the times – in stark contrast to what was in vogue

then, the poetry patterned after that of Jose Garcia Villa, preacher

extraordinaire of non-political literary writing.

The poems Sison wrote after the publication of Brothers and Other Poems show a decisive break with the poetic

tradition that influenced him in his earlier writing years. They still use

imagery and other poetic tools, to be sure – but in these Sison has taken

extra care to do so in a manner that more readers would be able to grasp.

Sison’s poems are suffused with various kinds of imagery, but in these one

thread is common – the voice of a poet resolved not only to write good poetry,

but also to revolt against oppression in all its forms. He thus shares, in

Philippine literary history, a place with the likes of Andres Bonifacio, Carlos

Bulosan, Amado V. Hernandez, Eman Lacaba, Lorena Barros, and Romulo Sandoval. Bulatlat.com

Back

to top

We

want to know what you think of this article.

|