This story

was taken from Bulatlat, the Philippines's alternative weekly

newsmagazine (www.bulatlat.com, www.bulatlat.net, www.bulatlat.org).

Vol. IV, No. 52, January 30 - February 5, 2005

Ever increasing

rates from the EPIRA

A closer look at

the electric power industry in the Philippines

Electric power is a basic need for households and industry. But despite being rich in potential energy sources such as geothermal, hydropower, coal, oil, and natural gas, the country was plunged into darkness because of 8 to 10 hr blackouts in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The government’s solution is to privatize the power industry. But far from benefiting power consumers, this has led to exorbitant increases in power rates. Worse, consumers are now hostages of IPPs shouldering even the losses of these companies.

By

Dr. Giovanni Tapang, Engr. Ramon Ramirez, Kim Gargar

Posted by Bulatlat

Electric power is a basic service that is needed by households in everyday activities and is equally important for industries to operate. The failure of the government to provide electric power was evident when the country faced massive blackouts in the late 1980s and early 1990s due to a shortage of power supply.

The response of the government to this power crisis was not to build the necessary infrastructure to meet the demand but to contract out power generation to independent power producers or IPPs. Furthermore, it has made steps to privatize the whole power industry effectively abandoning its role in providing electric power services and opening up the power industry to private companies.

During the late 18th century, the hacienda system had expanded the control of land by Spain and this spurred massive plantations of export crops like tobacco, sugarcane, abaca, etc. In order to hasten the exchange of goods and extraction of raw materials, transportation and communication facilities were developed. They constructed steamships, roads, more efficient seaports, railroads, and so on.

During the later part of 19th century, due to the urgent need of Spain, the first power corporation was born in the Philippines, the La Electricista that had 10 60-KW AC steam generators.

When the United States (US) replaced Spain in colonizing the Philippines in 1898 through the Treaty of Paris, it did not change our economic orientation but increased the amount of commercial crops and raw materials for export. Manufacturing and processing industries like sugar centrals, coconut oil refineries, rope factories, and other industries necessary for extracting and exporting raw materials from the Philippines were maintained.

In 1903, the Manila Electric Railroad and Light Company (MERALCO) was established to provide rail transportation and electric services in Manila. In 1905, after being awarded a 50-year franchise, MERALCO took over La Electricista’s business and its first 2,250-KW power plant was commissioned.

A year after the establishment of Philippine Commonwealth Government in 1935, the Commonwealth Act No. 120 creating the National Power Corporation or NPC as a non-stock, government-owned corporation was passed. After two decades, NPC became a stock corporation through RA 2641.

In 1972, two months after Martial Law was declared, PD 40 was enacted. This mandated NPC to construct generation and transmission facilities in Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. Moreover, NPC was tasked to own and operate a single integrated network for all power-generating facilities nationwide.

When NPC bought MERALCO’s thermal power plants in 1979 and this plant was integrated in the Luzon power grid, the total generation capacity of NPC increased by 90% and this made NPC the country’s dominant producer and supplier of electricity.

In 1987, EO 215 signed by President Corazon Aquino effectively deregulated the power generation sector. This was to fulfill the government’s commitment to prepare the groundwork for the eventual privatization of the NPC as pushed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The first build-operate-transfer (BOT) contract allowed by the EO was signed in 1988 with Hopewell, a Hong Kong-based firm, to construct and operate a 210-MW power plant (Navotas I).

The issues surrounding the privatization of NPC are mostly related to the power crisis and due to the government’s failure to address this critical shortfall in power supply. By 1991, the 6- to 10-hour daily blackouts were costing the Philippine economy an estimated $1 billion in lost output annually. To stave off the crisis, RA 7638 or the Department of Energy Act of 1992 was enacted to create the Department of Energy (DOE). DOE was tasked to develop and update the existing Philippine Energy Program (PEP) which shall provide for an integrated and comprehensive exploration, development, utilization, distribution and conservation of energy resources. As its policy response to the power crisis, RA 7648 or the Electric Power Crisis Act was enacted in the same year that the DOE was created. This further opened the door for the entry of private power corporations. DOE was tasked to boost the entry of these private firms in construction and operation of power plants.

The Electric Power Industry Reform Act or the EPIRA

Due to the pressure of creditors on the Philippine government to fast track the privatization of the power sector before the release of power reform program loans to finance the country’s power development program, the Electric Power Industry Reform Act, or the EPIRA, was railroaded by Congress and signed into law by President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo in 2001. The law was passed despite opposition from the people. EPIRA was the first major piece of legislation passed by the Arroyo regime, five months after EDSA 2. Power sector reforms and the sale of NPC to private business were long standing recommendations of the IMF. These recommendations were part of the structural reform program the country has to implement as a pre-condition for more loans. At that time, the country was trying to avail of loans from the Japan Export-Import Bank, Asian Development Bank (ADB), and the World Bank (WB).

The EPIRA seeks to restructure the electricity industry and privatize the National Power Corporation or the NAPOCOR. The government’s objective in privatizing NAPOCOR is to cut losses from loans and pass on the burden of power infrastructure investment to the private sector, while earning revenues from the sale.

Contrary to what has been promised during the passage of the law, the EPIRA has not caused any real decrease in power rates. Aside from the initial and fleeting 30 centavo Power Act reduction, there has been no decrease in power rates due to the EPIRA. Instead, the EPIRA has legitimized the onerous Purchased Power Adjustments from contracts entered into by the NAPOCOR. Even with the anticipated establishment of the wholesale electricity spot market (WESM) which would purportedly be the mechanism to identify and set the prices between sellers and buyers of electricity, the onerous bilateral contracts between distribution utilities and power suppliers would still be honored.

Cross subsidy removal would translate to an increase in power rates to residential consumers which by numbers would dominate the end-users of electricity. Even with discount schemes within customer classes, the removal of subsidies would at the least translate to a 71 centavo increase within 3 years. Note that this increase would already render useless the 30 centavo rate reduction.

The EPIRA was designed to reform the power industry not for the benefit of end users but for foreign transnational corporations. The various highlights of the EPIRA ranging from the creation of the National Transmission Company (TRANSCO), the Power Sector Asset and Liabilities Management corporation (PSALM), the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC), the wholesale electricity spot market (WESM), the unbundling of power rates and the various codes and rules implemented under the EPIRA are designed to segregate each saleable part of NAPOCOR, make it attractive to investors and create structures and offices to facilitate these transactions.

Furthermore, the EPIRA makes the national government assume P 200 B worth of NAPOCOR debts to make it viable for sale. This P200 B however would be recovered as stranded debts in future bills to end users. NPC debts will appear as part of the universal charge to be passed on to consumers.

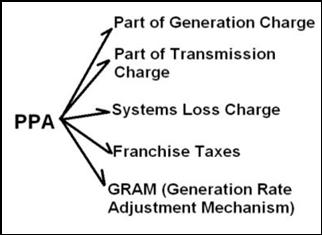

EPIRA integrates the independent power producers (IPP) and their onerous contracts into the whole power industry. These IPPs and the contracts entered into by the government and distribution utilities are the source of the PPA or the purchased power adjustment. The PPA remains to be a large part of electric power rates of end-users albeit under different names. With the unbundling scheme ordered by the ERC, the PPA was hidden and distributed in the various line items in the new electric bill such as the generation charge, the transmission charge, system loss charges, subsidies and franchise taxes.

These IPPs are mostly owned by foreign transnational corporations in partnership with big local power tycoons. At least twenty two out of the 41 IPPs are largely foreign owned. Five are partly or wholly owned by the Lopez family which also owns Meralco, and some others by regional distribution utilities. In the findings of an inter-agency committee tasked to review IPP contracts, only six out of 35 contracts were found to be without any legal or financial issues. The rest were supposed to be renegotiated by the government. Privatization actually facilitates the entry and control of national economies by foreign TNCs who, at present, are the dominant players among the IPPs. Only these foreign TNCs alongside a number of local power tycoons (Lopez, Aboitiz, Alcantara, etc) have the financial capacity to operate and maintain power generation, transmission and distribution, and even buy out the Napocor.

Excluding the US, Philippine IPP capacity exceeds that put up over the rest of the world combined, in terms of installed capacity. This would continue to increase with the full implementation of the EPIRA and the privatization of power generation.

The EPIRA brings about the exploitation and plunder of our natural resources for the benefit of these foreign companies. Far from improving our electric power independence by promoting indigenous energy sources, EPIRA has reduced taxes and royalties for those exploiting our resources. The EPIRA provides for the equalization of taxes and royalties on the exploitation of natural energy sources, which simply means the removal of taxes for the IPPs. Lost revenues due to the removal of royalties will be passed on to the consuming public via the universal charge. Under the bill to increase VAT rates to 12% being discussed in Congress, IPPs are already being exempted despite the fact that these companies are paying only 3% of their revenues as taxes.

In addition, the power of eminent domain, as provided for in the act (Sections 6 and 12), grants transmission and distribution companies prior rights over the country’s land resources and thus may evict the occupants or owners of the land in question. The dislocation of the indigenous peoples (IPs) from their ancestral domain and of other peasant settlers with the construction of power plants and other development projects over their claimed territories has been well documented

The EPIRA favors power industry players over consumer interests. It legitimizes the passing on of costs of power generation to end users. For example, the system loss charges appearing on electricity bills, passes on the inefficiency of distribution utilities to end users. Other line items in the unbundled bill such as the missionary electrification and environmental charges pass on the costs of installing new electric power lines and the environmental maintenance of power utilities to the general public. Stranded costs and debts by both the NAPOCOR and power utilities are also to be recovered from the general public under the item universal charge.

The EPIRA has put as policy the full recovery of “prudent and reasonable” economic costs of a distribution utility. As a result, distribution utilities now recover and pass on currency fluctuations, fuel cost fluctuations as well as contract obligations (PPA) to the end-users. The mechanisms approved by the ERC such as the Generation Rate Adjustment Mechanism (GRAM) and the Incremental Currency Exchange Rate Adjustment (ICERA) are concrete examples of these. The power industry will be a risk-free business because of all these pass-on charges.

The unbundled rates, even with the discounts, hit the smallest end users hardest. Small end users, even with the 50% discounted rates, still pay 159% more than their real electricity costs. Higher users of electricity would pay from 120% (100 kWh) to double (more than 500 kWh) their real electric costs.

The EPIRA has not brought about and will not bring about a stable electricity supply to the whole country. In 2003, the total installed capacity in the country was 13,380 megawatts, of which 11,191 megawatts is the actual dependable capacity. Current peak demand is 67% of dependable capacity or 7,497 megawatts. The Philippines has an excess capacity of around 11% factoring buffer requirements. This has changed in 2004, where the country's total installed generation capacity stood at 15,763 MW and its dependable capacity at 14,008 MW. Our peak demand is 9,069 MW and thus overall, we have the capacity to provide for our electricity needs. However, interconnections of major islands are needed to distribute this power capacity throughout the country.

It is indeed true that the construction of power plants will still have to continue but the government, through the EPIRA, makes sure that the IPPs will play a key role in providing electricity. However, there is no guarantee that IPPs would maintain a power plant in the long run. As soon as the location becomes a liability to the private company’s profit margins, they can and will shut down operations. This can be seen in the threats some years ago of the Cebu based Cebu Private Power Corp (CPPC) that it will shut down operations of its 65 MW plant due to financial constraints further aggravating the projected shortage in the Visayas. Such moves make the development and industrialization of our country hostage to the whims and profit margins of the private industry players.

Why are power rates so high?

Energy is a necessary factor for industrialization and the Philippines is rich in a variety of fossil and renewable energy sources. Despite this, no significant industrialization activity has taken place in the country. If we look at the distribution of energy sales (1999), 90.8% of the total energy sales go to households and small businesses (residential and commercial) while only 8.2% come from sales to industries.

This implies two things: that the country lacks industries to utilize the production of energy and it is the relatively smaller consumers of electric power (mostly households and commercial buildings) that are most affected by rate increases.

In December 2004, a consumer will pay at least 28% more in electricity bills compared to December 2003. A household consuming 150 kWh per month will effectively be paying P7.20 per kWh in December 2004 compared to P5.61/kWh in December 2003. The 28% increase is mainly due to the provisional authority granted by the Energy Regulatory Commission to the National Power Corporation (NAPOCOR), for increases in transmission rates, previous adjustments in generation rates due to the Generation Rate Adjustment Mechanism or GRAM as well as adjustments in the currency exchange rates. Those with 70 and 100 kWh monthly usage are going to pay 23 % and 22% more, respectively.

The EPIRA mandates the unbundling of rates for generation and distribution utilities. The unbundling of rates is consistent with the privatization thrust of the EPIRA wherein the power sector is segregated into generation, transmission and distribution sectors in order to determine the profitability of each. The unbundling of rates also aims to show the “true cost of power” and has thus been used as a vehicle for increases in power rates. When Meralco unbundled its rates in 2003, this resulted in an increase of 17 centavos/kWh.

With the unbundling of rates, customers now see the different components of the electric bill, such as generation charges, transmission charges, systems losses, distribution charges, meter charge, franchise taxes and other add-ons under the universal charge. Notice that the PPA no longer appears in the monthly bills. Still, power rates remain at a record high.

Comparative Rates for December 2003 and 2004

The so-called discounts for users with monthly consumption of less than 100 kWh are deceptive to say the least. Those using 50 kWh will be paying 36% more this year. These discounts are in reality paid for by other consumers and not by the government or Meralco.

As of June 2004, residential power rates in the

Philippines is the fourth most expensive in Asia after Japan, Hongkong and

Cambodia. Philippine industrial rates rank seventh in Asia after Cambodia,

Japan, India, Hongkong,

Indonesia and China, according to the DOE.

Compared to1990, when the average cost of power was P1.83/kWh, the cost of electricity now amounts to at least P5.58, a 300% increase.

Source: 5th status report on EPIRA Implementation, May 2004-October 2004, Department of Energy

The Purchased Power Adjustment (PPA) and IPPs

With the mothballing of the 650-megawatt US$2.2-billion Bataan Nuclear Power Plant in the mid-1980s, no buffer for increased power demand by industries and households was constructed nor planned. By the early 1990s, this resulted in daily 8 to 12-hour blackouts. Citing lack of sufficient funds to construct power generation facilities to adequately meet present and future demands, the Ramos administration enticed foreign and private-sector investors into the country’s electric power industry using such measures as the Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) program.

By 1998, an estimated US$6 billion was spent by IPPs to construct and operate power generation facilities with a total capacity of 4,800 MW. A year after, half of total energy sales in the country were already sourced from IPPs. As of December 2001, Napocor’s IPPs accounted for 31%, or 3,667 MW, of the total generating capacity and non-Napocor IPPs (such as those owned by the Lopezes, First Gas and Quezon power) provided the remaining 1,168MW or 10% of the total generation capacity.

This generation capacity was not obtained cheaply. With the onerous take-or-pay provisions, Napocor has to pay the IPPs the capacity for generation whether or not power was actually generated. Higher rates resulted from the NPC’s recovery of these losses through the controversial Purchased Power Adjustment (PPA). By June 2002, the PPA constituted more than half of the electricity charges paid by consumers.

Additional costs are incurred when Napocor has to deliver fuel on-site to provide tax-exemptions for the IPPs. Furthermore, contracts are dollar-denominated, making Napocor obligations vulnerable to foreign exchange fluctuations.

Due to massive protests and public outrage over the PPA, President Arroyo ordered in May 2002 the suspension of NPC’s PPA collections, limiting it to only 40 cents/kWh from the previous P1.25/kwh. NAPOCOR sustained losses amounting to P29B per year since 2002 because of its failure to collect its PPA. The President’s actions resulted in an artificial lowering of rates which would later be negated by NPC’s rate increase.

Many of the losses incurred by the NPC were due to obligations to IPPs. Firms such as KEPCO, Edison Global, Mirant and others billed us for 27.27 billion kWh while only delivering 19.15 Billion kWh in 2002. We paid around 30% more of what we actually consumed.

The Generation Rate Adjustment Mechanism (GRAM)

The GRAM was designed essentially as a replacement for the recovery of the PPA. Like the PPA, it is also a monthly automatic cost recovery mechanism but this time without the notoriety that the PPA has earned.

The ERC in its approval of the unbundling of Meralco rates has acknowledged that

“The current PPA is allocated between the generation and transmission rates. The generation component shall be periodically updated through the Generation Rate Adjustment Mechanism (GRAM).”

-ERC Order dated 30 May 2003, page 9

For example, Meralco’s generation charge continues to increase because of GRAM recoveries. Meralco merely has to submit records of purchases from their IPPs and they are allowed to recover extra costs, without need of hearings and verification from the ERC. Consumers can be automatically billed for electricity that was not delivered, so long as the onerous contracts remain.

Thus with the unbundling of rates, the PPA is now being paid for under five new line items in the electricity bill as diagrammed below:

Recovery of foreign currency exchange losses through the ICERA

Automatic recovery of losses, designed and approved by the Energy Regulatory Commission, such as the ICERA or the incremental currency exchange rate adjustment, is another burden on the people. The ICERA is a risk-free formula for power monopolies because it insulates them from any foreign exchange fluctuations.

Reduction of cross-subsidies

Residential consumers paid an additional 28.52 centavos/kWh starting October 2004 because of the 40% reduction of the interclass cross subsidy. The EPIRA mandates that all subsidies will have to be removed within 3 to 10 years, with the lifeline rate subsidy for consumers using less than 100 kWh being the last to go. By October 2005, residential consumers will have to pay an additional 42.78 centavos/kWh and lifeline consumers will lose their discounts around 2010. The total removal of inter-class subsidies will result in an increase of 71.30 centavos/kWh.

The mathematics of power rate discounts: The poor subsidizing the poorer

Malacanang's attempt to cushion the blow of the hefty power rate increases on the poor is through the so-called 50-percent lifeline rate discount. This subsidy is taken from 65% of the customer base and is not due to any concern or interest of our government to alleviate the burden of rate hikes on consumers. It is more of a case of the poor subsidizing the poorer. Commercial and industrial electricity users pass on the costs of these subsidies as price increases to consumers.

For example, given a test month in 2003, Meralco lost P134,923,561 due to discounts for consumers using 100kWh or less. However, Meralco was able to collects 7.61 centavos/kWh from the residential consumers using 101 kWh and above and from commercial and industrial consumers. Given the total kWh consumption of these consumers in one month multiplied by 7.61 cents/kWh and we get P152,474,582. This is P17,551,021 more than what they lost from the discounts.

Presently, consumers using 100 kWh and below get the following discounts:

|

Monthly consumption (kWh) |

No. of Customers (2002) |

Discount |

collection from lifeline rates |

|

0-50 |

661,716 |

50 % |

- |

|

51-70 |

299,737 |

35 % |

- |

|

71-100 |

465,236 |

20 % |

- |

|

101-200 |

1,257,820 |

- |

0.0761 |

|

201-300 |

564,417 |

- |

0.0761 |

|

301-400 |

258,133 |

- |

0.0761 |

|

over 400 |

415,648 |

- |

0.0761 |

|

|

|

|

|

These discounts apply to the generation, system loss, distribution, metering and supply charges. The above is called by its technical term, lifeline rate subsidy. Those using above 100 kWh presently pay an additional 7.61 centavos per kWh that is used to subsidize the lifeline consumers who are using less than 100 KWh (which is really a case of one section of consumers subsidizing another section of the consumers).

In this discount scheme, Meralco, NPC and President Arroyo are happy since they earn brownie points while hiding the reality that none of them shelled out any centavo to alleviate the burden of high electricity rates.

Other recovery mechanisms

In summary, the PPA has not been removed. It has been hidden within the generation charge, the transmission charge, the system loss charge, franchise tax and other charges. If the PPA were truly gone, electric bills should have gone down by 50%.

Power consumers would have to prepare for the eventual imposition of the Transmission Rate Adjustment Mechanism (TRAM) which would pass off the costs of transmission companies to the people, similar to the function of GRAM. Any changes in the cost of the transmission of electricity through the transmission towers will be shouldered by the people.

The other "pass-through" charges are also really pass-on costs to consumers. Generation charges are computed with a 60-40 mix of National Power Corp. (Napocor) and Meralco power plants. About 53 percent of this cost is remitted to Meralco's independent power producers (IPPs), most of which charge nearly twice as much per kilowatt-hour as Napocor plants.

The systems loss, including pilfered power and

the electricity used by Meralco offices and facilities, is passed on to us at a

rate of 69.65 centavos per kWh. Because of this, Meralco's technical system loss

(i.e. excluding pilferage) has not been reduced for the past years. This means

Meralco has not seriously tried to become more efficient. But it goes after

pilferers since they can recover twice of their losses, once from the pass-on

cost as part of the systems loss charge, and another courtesy of the

Anti-Pilferage act which allows them to charge the households the estimated cost

of their pilferage.

More pass-on charges include the metering charge and franchise and local taxes. Other pass-on costs are under universal charges, which include many other components such as the missionary and environmental charge. The missionary charge is a compulsory contribution to a fund to be used for electrifying remote barangays because no businessmen would like to invest in those areas where there are only a few customers. But why are we charged for a job the government should be doing?

This is also true of environmental charges. Why are we charged for the havoc that the generation plants of Napocor or these IPPs do to the environment?

Unbundling has increased power rates and it will continue to increase because of the new charges, the passing on of the P200-billion stranded cost and debt recoveries of the NPC and the eventual removal of subsidies. All these mean higher electric rates for all.

Electric cooperatives

An electric coop (or REC, or rural electric

cooperative, the legal nomenclature used) is owned and

managed by the consumers who are also its members. They elect the members of the

board and appoint a General Manager to manage its day-to-day operation.

An REC can be either a non-profit non-stock or a stock coop. In a stock coop,

the member/consumers own stocks and can be paid out dividends when a profit is

made. Sorsogon Electric Cooperative II is an example of a stock coop where the

member consumers buy stocks on monthly installments, many at P5.00 per month up

to a certain maximum.

A coop may or may not be registered with the Cooperative Development Authority (CDA).

If registered, it is exempted from income and other taxes. Both are supervised

by the CDA as far as their coop legal responsibilities are concerned.

Since distribution is still regulated under the EPIRA, a coop must file for its

power rates with the ERC (Energy Regulatory Commission) before it can bill its

customers. In its application for power rates (or tariff) the coop factors in

its O&M (operation and maintenance) expenses, a reinvestment fund (for upgrades

and expansion), other expenses that may be allowed by the ERC, and the desired

RORB (Return on Rate Base) which is the provision for profit so that members can

have dividends. If the coop is non-profit, non-stock there is no such provision

so that the power rate would be lower. Normally though member/consumers of stock

coops would not mind a higher electricity rate because they would share in the

profit.

The big difference then between an REC and a private Distribution Utility like

Meralco or Davao Light is the nature of ownership and control of the utility.

Ideally, the consumers themselves own, control and manage the coop and any

profit made (if stock coop) is shared among the consumers who are also the

people in the community.

With a private DU, any profit made is shared among the private owners. Since the

objective of businessmen is to maximize their profit you will easily understand

why such racket as the overcharging case of Meralco happened, where it had to

pay us back P29B in overcharges illegally collected in ten years.

Because they are currently deep in debt, many coops are also being considered

for privatization through what is called an Investment Management Contract (IMC).

Under an IMC, a private company can buy-out the coop after 5 years of management

and control. These IMCs are going to be part of the strategic plan to privatize

wholly the power sector.

The role of foreign interests in the privatization of the power industry

It was not a secret that President Arroyo railroaded the signing of the EPIRA due to pressure by creditors on the Philippine government before they release the power reform program loans to finance the country’s power development program. The recent NPC application for rate increase was also clearly due to a pressure from the creditors of the NPC.

Interestingly, the training of staff, the website as well as some of the consultants of the ERC are provided for or have links with AGILE, a USAID program that seeks to facilitate liberalization of our economy.

According to US Department of Energy, “the Philippines is important to world energy markets because it is a growing consumer of energy, particularly electric power, and a major potential market for foreign energy firms.”

Energy sources of the Philippines

The Energy Information Administration of the Department of Energy of the US has enumerated the following main sources of energy in the Philippines: geothermal, hydropower, coal, oil, and natural gas. All of these contribute to the country’s energy production, which is concentrated in the electricity sector.

Oil production in the country remains flat and far below oil consumption. Oil consumption on the other hand has been increasing since 1986 up to the present. Despite small proven oil reserves, companies, like Australia-based Nido Petroleum (formerly Sydney Oil Company Drilling and Exploration), that are into oil explorations in the northwest and southwest Palawan Basin, the Cagayan Basin, and other small concessions elsewhere in the country believes that significant quantities of oil may be recoverable.

The Philippines has 2.8 trillion cubic feet of proven natural gas reserves. In the largest natural gas development project in the country and one of the largest-ever foreign investments in the country, Shell Philippines Exploration (operator, with a 45% stake), Texaco (45%), and the Philippine National Oil Company (PNOC, 10%) has tapped the Malampaya natural gas field’s estimated 2.5 trillion-cubic-feet reserves. Gas from Malampaya will fire three power plants with a combined 2,700-MW capacity for the next twenty years, and could replace as much as 50% of the oil that the Philippines currently imports for power generation.

Coal is the Philippines’ largest source of fossil energy production but 82% (1998) of total coal consumption is imported.

Geothermal power accounts for the country’s largest share of indigenous energy production, followed by hydropower, coal, and oil and gas. The Philippines is the world’s second largest producer of geothermal power, after the United States. The country is located in the volcanically active “Ring of Fire”. As of April 2000, Geothermal power makes up around 17% of the Philippines’ installed generation capacity, most of which has been developed by the Philippine National Oil Company-Energy Development Corporation (PNOC-EDC).

The Philippines does have significant amounts of hydroelectric potential. The most notable development, the Agus units, has been built at the Maria Cristina Falls on northern Mindanao, which makes for 32% of the country’s total hydroelectric power as of December 1999. Hydroelectric power on Luzon accounts for the largest share to the total hydroelectric power generation (1,280 MW, 56%).

According to EIA, electricity demand is expected to grow almost 9% per year until 2009, necessitating almost 10,000 MW of newly-installed electric capacity. As of 1999, the total electric power generation is 12,050 MW. The National Power Corporation (Napocor) provides a total of 5,400 MW (45%) of electricity while various independent power producers (IPPs) provide the remaining 6,650 MW.

Southern Energy, a wholly owned subsidiary of Consolidated Electric Power Asia Ltd. (CEPA) of Great Britain, is the Philippines’ largest IPP and operates five power plants in the country. Southern’s new coal-fired Sual plant began commercial operation in late 1999. The 1,218-MW plant is about 130 miles north of Manila and reportedly is the nation’s largest electricity producer. Napocor is the sole purchaser of Sual electricity.

Texas-based El Paso Energy International and Hawaiian Electric Industries in February 2000 formed a 50-50 joint venture to own and operate five power plants now owned by East Asia Power Resources Corporation, a public Philippine company. The total generation capacity of the venture’s holdings will be 390 MW. The plants are located in Manila and Cebu.

Actually, there is an oversupply of power generated by the Napocor power plants and those of the IPPs combined. Honoring its Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) with the IPPs, the NPC had to retire the operations of its power generating plants to accommodate the higher priced power generated by the IPPs.

Indeed, the Philippines is rich in energy sources and it seems that explorations for such resources is endless. In late 1999, the Philippine and Spanish governments agreed to a plan whereby Spain would assist in bringing solar power to some of the Philippines’ rural areas. Finland plans to help fund a project to electrify 10,000 homes in the rural Antipolo area with methane generated by the San Mateo landfill, following the landfill’s December 2000 closure. In cooperation with the Netherlands, the Philippine government is planning to expand its wind energy capacity. DOST estimates that wind resources could generate 70,000 MW of power.

Power to the people

The Philippines’ rich energy sources did not result to economic prosperity for the Filipino people. The EPIRA has only resulted into ever increasing power rates, the plunder of our natural resources, the intensifying control of foreign TNCs over our power industry and our economic development as a whole. Furthermore, it has shown the vulnerability of the government to pressure and dictates of huge foreign banks and financial institutions

In the case of power, water and fuel, the role of a public utility is to generate or procure these resources, deliver and distribute it to the public. In the case of transportation and telecommunications services, the public utility provides the infrastructure and means that enable people to take advantage of the goods and services inherent to the utility. Power, water and fuel utilities provide access to electricity, water and fuel to households and industry. These utilities should be accessible and affordable to the people. Limiting access by increasing the costs of these services would make, in general, daily activities more difficult for the people.

Nationalization of public utilities is important since these public utilities are strategic in nature to the development of the country. It provides the necessary infrastructure and support to the people’s daily activities and industrial growth. If these industries are left to foreign monopoly control, whose interest is to recoup their investment and rake in profits--- we would lose quality of service. The people will be faced with an unending increase in utility costs and our national interest would be compromised.

In particular, electric power is a basic service that should be provided to the people and is an indispensable factor required in genuine industrialization. The government’s excuse of having no funds to build the requirements of the power industry is a false claim because it can shell out hundreds of billions of pesos to debt servicing and military spending. Furthermore, it gives numerous incentives and sweetheart deals to foreign investors.

The privatization and deregulation of electric power by the EPIRA runs counter to the interests of the Filipino people. Government should invest in and develop the power sector to serve national industrialization and development. It has been argued that government is inefficient and corrupt and thus makes it incapable of running the power industry. The call for nationalization must also go hand in hand with the struggle for good governance, whereby the government truly represents and upholds the interests of the people. Furthermore, alternative sources of power that are low-cost and environment friendly should be promoted and developed.

The government should pursue genuine nationalization of the power industry instead of neoliberal power reform if it is truly serious about bringing down the electric power rates. Posted by Bulatlat

References:

1. Energy Information Administration, US Department of Energy, http://www.eia.doe.gov

2. PNOC-Energy Development Corporation, http://www.energy.com.ph

3. Compton’s Encyclopedia Online 1998

4. FAQ Sheet on House Bill No. 8457, Committee on Energy, House of Representatives

5. Complete privatization of Napocor: private power, IBON Special Release 38, October 1998

6. Power reform or privatization, IBON Special Release 52, April 2000

7. Ang Panganib ng Pribatisasyon, prepared by ACT, AHW, COURAGE, CONTEND, and HEAD for the People’s Summit, July 19, 2001

8. Meralco Employees and Workers Association Press Release, May 26, 2001

9. Power play causes delay, article by Marcelo E. de la Cruz and Pablo C. Villasenor

10. 5th status report on EPIRA Implementation, May 2004-October 2004, Department of Energy

11. AGHAM files and press releases

About the authors:

Dr. Giovanni Tapang is the chairperson of the scientist group Agham and is one of the convenors of the People Opposed to Warrantless Electricity Rates (POWER). He teaches at the National Institute of Physics in UP Diliman.

Engr. Ramon Ramirez has been an activist for three decades now and was a former political detainee. He too is a member of Agham and a convenor of POWER. Ramirez topped the electrical engineering board exams in 1967.

Kim Gargar is a member of Agham who graduated magna cum laude from the UP National Institute of Physics, He is currently the chair of the Department of Physics at the Mindanao Polytechnic State College.

Ako

ni Elektrokyut ng Anakpawis

(with apologies to the kid in the TV ad)

Gastos sa:

Generation charge...ako

Transmission charge...ako

Systems loss charge...ako

Ninakaw na kuryente...ako

Kuryenteng di naman nila nilikha...ako

Kuryenteng di ko naman ginamit...ako

Kuryenteng di nasukat dahil sira pala ang metro...ako

Kuryenteng ginamit ng Meralco sa nga opisina

nila...ako

Gastos sa:

Distribution charge...ako

Supply charge...ako

Retail customer charge...ako

Metering charge...ako

Discount para sa mga poor lifeliners...ako

Discount ko, binawasan na ako

Overcharging ng Meralco...ako

Gastos sa:

ICERA dahil sa pagtaas-pagbaba ng dolyar...ako

Local franchise tax...ako

National franchise tax...ako

Noon nga pati income tax...ako

Buti na lang nagreklamo at nanalo ako

GRAM sa pabago-bagong gastos sa paglikha ng

kuryente...ako

Pakuryente sa mga liblib na pook, alyas missionary

charge...ako

Para sa pag-alaga sa kalikasan, alyas Environmental

charge...ako

Gastos sa:

12% Return on Rate Base o Kita ng Meralco....ako

8% Return on Rate Base o Kita ng NPC...ako

P24 Bilyon kita ng Mirant noong 2002...ako

P4.6 Bilyon kita ng Lopez' First Gas Power noong

2002...ako

Bilyon-bilyong kita ng iba pang IPPs at power

utilities...ako

Milyon-milyong suweldo ng mga executives nito...ako

May mga darating pang gastos sa:

TRAM na pabago-bagong gastos sa pagdeliver ng

kuryente...ako pa rin

kahit na alam kong tinaTRAMtado na nila ako

Bilyon-bilyong stranded debts ng NPC...ako pa rin

Bilyon-bilyong stranded contract costs ng NPC...ako pa rin

Equalization taxes and royalties...ako pa rin

Lagi na lang ako.

Lahat din lang naman ang gumagastos ako

I-takeover ko na lang kaya ang NPC, Mirant, mga IPPs at Meralco.

Pagkatapos ako ang magiging may-ari....si Juan de la Cruz, ako!

© 2004 Bulatlat ■ Alipato Publications

Permission is granted to reprint or redistribute this article, provided its author/s and Bulatlat are properly credited and notified.